Peter Mallory’s Presentation to the Annual Rowing History Symposium, Henley 2015

Historian Peter Mallory has graciously allowed us to share with Lucy fans his marvelous story of Lucy’s accomplishments as they fit into rowing History. This has been reproduced with Peter’s permission from his “The Sport of Rowing....a Continuing Journey” Blog.

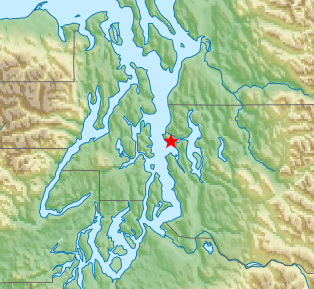

Washington Territory, the northwest corner of the US. What was it like in the early days?

Spectacular mountains, mighty rivers, great natural harbors, primeval forests, a temperate climate thanks to Pacific Ocean currents . . . and LOTS of rain.

The University of Washington was founded at what was then the western boundary of the civilized world in 1861, a century and a half after the great universities on the American East Coast. By the turn of the 20th Century, the university’s home, the rugged frontier city of Seattle,

perched between Puget Sound to the west and Lake Washington to the east, was growing like a weed, dominated by the lumber industry, building projects everywhere, and a steady influx of people from the American East as well as Europe and the Pacific Rim, all seeking jobs and opportunities.

Ellen Ernst, who has led the way in researching women’s rowing at the UW, believes that the region was naturally more forward-thinking concerning women precisely because it was the edge of the frontier, and they were used to having women working in the fields and clearing the land. The first UW graduate was actually a woman, a century before undergraduate women were even admitted to Harvard or Yale. Washington became a state in 1889 and granted women the vote in 1910, 10 years before the right was added to the U.S. Constitution and 18 years before the Representation of the People Act settled the matter in England.

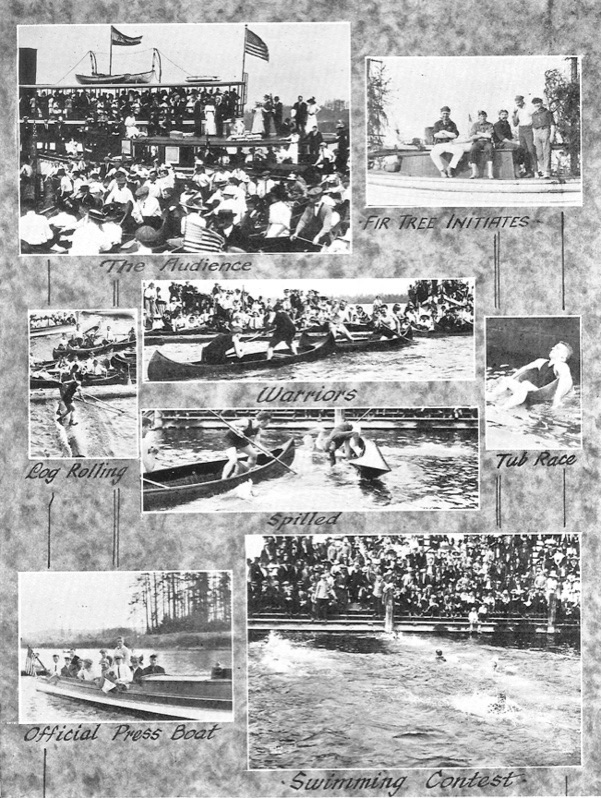

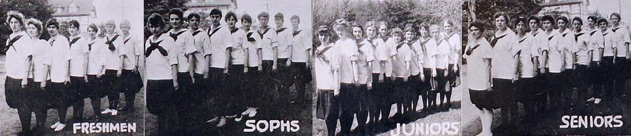

In the early decades of the 20th Century, every student at the UW was expected to take gymnasium classes or participate in a sport each term for a minimum of 2 years. For women, the choice of sports included basketball, handball, tennis, field hockey – and rowing. According to the college yearbook, 10 women started rowing at the UW in 1903. Also starting in 1903, the University put on an annual springtime Junior Day celebration, and given that the campus was literally surrounded by water, intramural aquatic events played a prominent role,

and almost from the beginning, women’s rowing was included. In fact, the yearly intramural Junior Day competition between class crews became the only possible end-of-year competitive focus for the UW women rowers since they believed they were the only collegiate women’s rowing program in the entire United States, and often proudly described themselves as such.

In fact, there is clear evidence of the existence of women’s rowing on a number of campuses in the American East during this period, but, like at the UW, all were intramural, and the subject of early women’s collegiate rowing, largely ignored to this day by almost all rowing and collegiate historians, still awaits proper attention.

Incidentally, the University of Washington is only a very recent exception to this. The reason I am able to speak to you today with some authority about the early history of UW women is that during the last decade Ellen Ernst went back and pored through century-old yearbooks and national, Seattle and campus newspaper archives. I stand on her broad shoulders.

One Eastern women’s collegiate rowing program that seems to have had a continuous history down to the present is that of Wellesley College,

outside of Boston. Physical education had been encouraged since the all-girls school opened its doors in 1870, its students participating in walking and gymnasium exercise. Rowing was added in 1875, and the boats were judged on "good form" as opposed to speed.

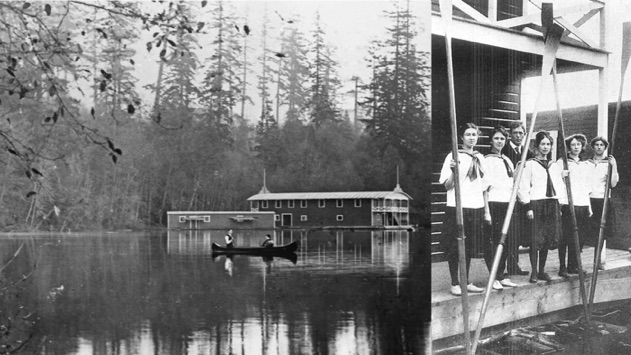

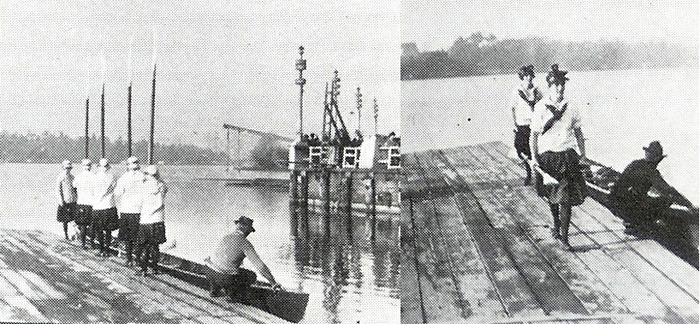

Back in Seattle . . . the Washington women rowers were racing each other on the water . . . with frequent enthusiastic impromptu competitions back home to the boat house from the half-mile buoy.

They trained in heavy, stable four-oared

and eight-oared barges (much like modern-day wanderrudern boats),

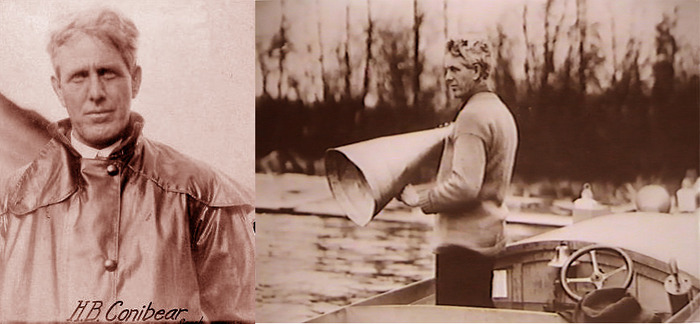

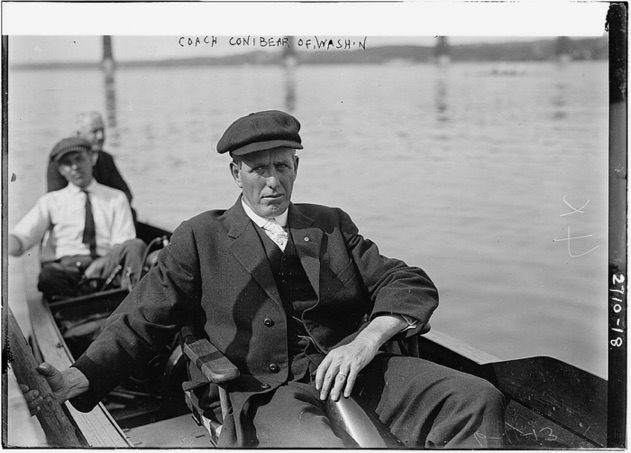

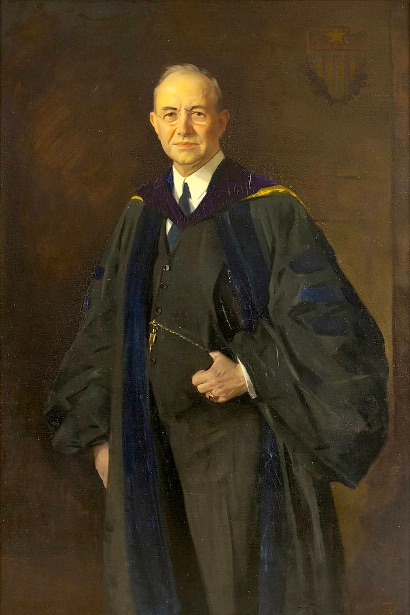

Hiram Conibear

was hired by the UW in 1906 to be the athletic trainer for the football and track teams. He soon volunteered to coach the men’s crew, and rowing quickly became his sole focus.

Conibear was a natural promoter and determined organizer who sought out as many members of the university community as possible – women as well as men – to become part of his program. Almost daily he visited the campus newspaper and was always available to comment on the activities of the men’s and women’s crews.

This isolated wilderness site on the shoreline of Lake Washington is actually only a short walk from the dormitories!

Junior Day in 1907 featured a spirited half-mile race between the Sophomores and Freshmen, the latter breaking it open half-way through and winning by five lengths.

Shortly before Junior Day the following year, Miss Lavinia C. Rudberg,

Gymnasium Director of Women, following the tenor of the time, announced: "The racing this year will not be a mere test of speed, but will include good form." This will turn out to be a bad portent for the future.

Nevertheless, the 1908 Junior Day race came off as a test of speed after all, the Freshmen beating the Sophomores off the line, never surrendering the lead down the one-mile course and winning by half a length. The college newspaper prominently mentioned that "both crews rowed in excellent form," perhaps in deference to Miss Rudberg.

Then in the fall of 1908, with 51 freshmen turning out, the administration partially disbanded the women’s rowing team. The plan was to only let those sophomore women who had made the team the previous spring continue to row. This would not be the last time that the "upper campus" (as in everywhere but the boathouse) would make an effort to rein in Conibear’s program on the wilderness fringe of the university, which was so difficult for them to supervise.

The head of the gymnasium department stated that he supported outdoor sports for women but wanted freshman women to do indoor work during the fall semester because "rowing for women is strenuous, and freshmen need to be under the supervision of the Physical Director for one term in order to satisfy the department that those electing rowing have the strength and health to undertake it."

However, articles in the campus newspaper imply that among the women turning out that fall at the boathouse were a number of freshmen secretly training with Conibear in addition to working in the gymnasium three days a week as they had been required.

Women turning out for crew actually outnumbered the men in 1909. One day in February, almost ten percent of the total university student body showed up for crew practice.

In March, Miss Rudberg organized a form contest with the following points breakdown – "10 for loading, 10 for the stroke oar, 10 for starboard stroking, 10 for port stroking, 10 for starboard backing, 10 for port backing, 10 for coxswain, 10 for general position when ready to stroke, 10 for all backing and 10 for unloading." A perfect score of 100 was possible. "The idea will be to show which crew has acquired the best rowing form, no attention being paid to racing or speed work."

The winning Freshmen "excelled in backing, both altogether and port and starboard singly. Their stroke also won more points, and their coxswain made the best landing."

In April 1909, Conibear organized the first All-University Regatta with reporters from The Seattle Times, The Seattle Post-Intelligencer and The Seattle Star along with the editor of the student newspaper and student members of the University Board of Control riding in the launch. The women raced for speed over a 600-yard course.

The following year, 1910, Miss Jessie Merrick, the new Gymnasium Director and Physical Instructor of Women, announced that she would not allow women to race, AT ALL! Form competitions only!

An editorial in the college newspaper stated: "[Now] threat is made to prohibit co-ed crew contests of speed and endurance. Women have the racing instinct as well as men, and no ‘form’ match will satisfy them, so let speed contests continue. Washington women are tired of being pampered into weaklings."

An opposing editorial stated: "From the editorial in a recent Daily, the ideal of women’s athletics would seem to be the cultivation of the 'racing instinct.' This is exactly the point upon which those who take the opposite view base their objections. Women are not physically constructed for great tasks of endurance, and a better ideal would be a more perfect self-control, the highest development of which she is capable."

Soon thereafter, a sign appeared at the shellhouse:

"I like rowing very much; I like racing better."

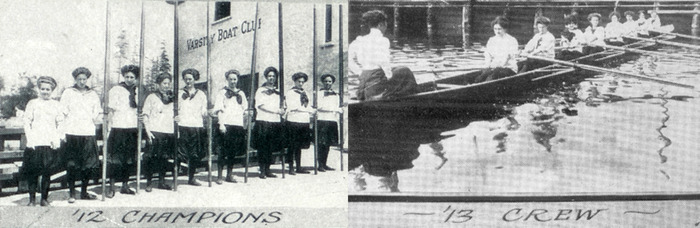

The Sophomores, Class of 1912, won the 1910 Junior Day form contest.

Remembering the 1910 season decades later, one participant said: "While the girls’ program was not supposed to be competitive in the least, it was not unusual for two or more girls’ crews to compete unofficially when out of sight of the boathouse."

No surprise, what with human nature . . .

When things looked like they couldn’t get any worse, in October 1910, the Gymnasium Director recommended that women’s rowing be discontinued immediately because rowing was too hard for women. The faculty then formally canceled women’s rowing at the UW.

This would indeed seem to signal the inevitable end of my presentation this afternoon . . . but the UW women were nothing if not resilient. Six months later in April 1911, an independent women’s rowing club was organized. They resumed training twice weekly for the coming Junior Day regatta and planned to divide into clubs named for suffragette leaders of the day, this being only one year after women in the State of Washington had won the right to vote.

In the winter of 1912, there was still a formal ban on women’s rowing when Coach Conibear

decided that he was no longer willing to coach women.

"I took up coaching of girls’ rowing in 1907. I had a nucleus of 5 girls turning out,

and around these I built up a strong crew. In the spring of 1910, 70 girls were rowing and I planned to hold some regattas, but the authorities frowned on the races, and women’s racing was abandoned. I would be glad to instruct the girls if the matter of management was left entirely in my hands . . . "

This last sentence is very telling as to Conibear’s true state of mind in deciding to no longer coach the women under the circumstances imposed upon him. It wasn’t about gender. It was about his desire for noninterference from upper campus.

But the upper campus was nothing if not contrary when it came to Hiram Conibear. Ironically, within two months Coach Conibear’s university contract was renewed for two years under the stipulation that "His duties are to include coaching any student of the university, male or female, in rowing." Despite this, there is no record of organized women’s rowing in the spring of 1912.

-----------------------------------------

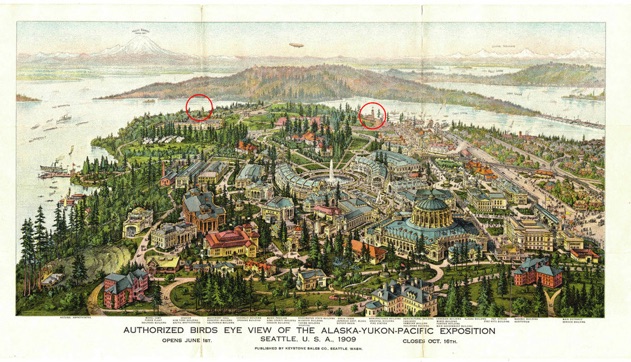

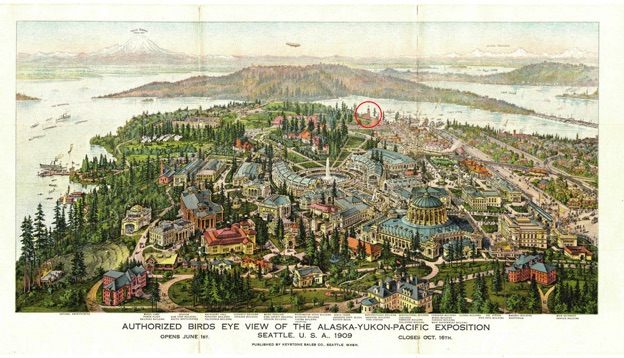

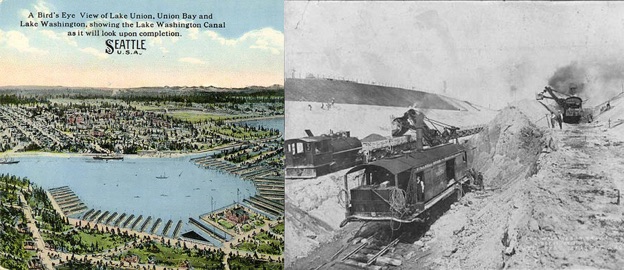

Now we must turn back to the fall of 1909 for a geography lesson.

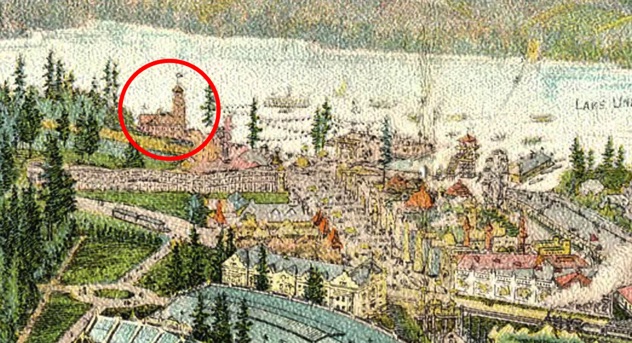

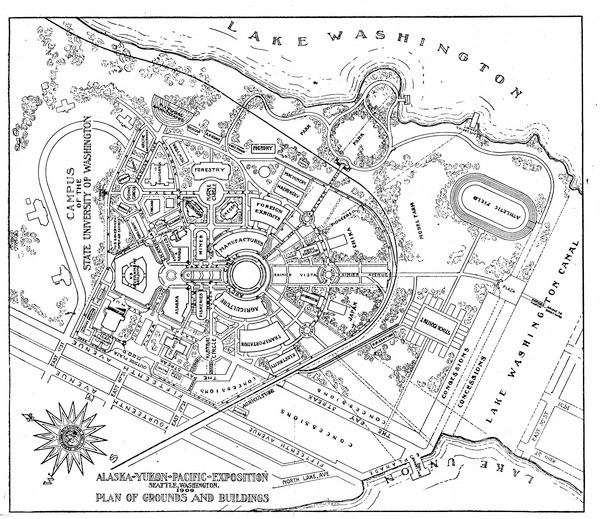

At the conclusion of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, the grounds of which had encompassed the University of Washington campus, Conibear had relocated the men’s and women’s crews from their rustic quarters along the forested shores of Lake Washington on the southeast side of the campus (left circle) to Portage Bay on Lake Union on the southwest side of the campus (right circle). Let’s take a closer look.

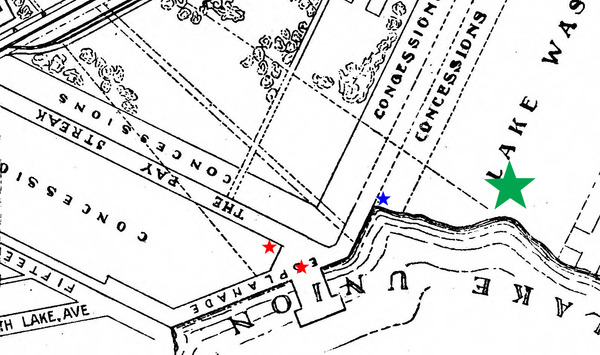

The teams moved into the former Coast Guard Lighthouse (circle) at the end of the Exposition's entertainment and concessions area known as The Pay Streak (the north-south avenue at the center of the above image).

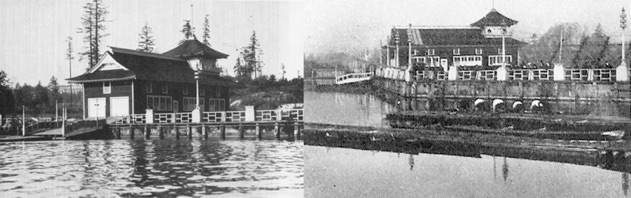

Here is the building during the Exposition at left and then after its conversion at right.

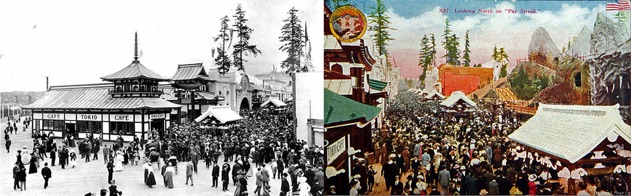

Now, three years later, over the summer of 1912, with explicit orders to accommodate both men and women, Conibear arranged to also take over the abandoned Tokio Café, a nearby building at the very end of The Pay Streak that had originally been part of the Japanese Pavilion, moving the structure perhaps 100 feet to a site right on the shore of Portage Bay next door to the Varsity Boat Club.

Here are two views of the café at its original location during the Exposition. (Note that a section of its roof along with the sign over its door are visible at the left edge of the right image.)

Conibear’s plans for the building were two-fold. First, he intended that boatbuilders Dick and George Pocock from Eton in England, whom I will discuss in the second half of my presentation, that the brothers Pocock would build racing shells for the university on the upper floor, and, second, that the reauthorized women’s rowing program would occupy the ground floor.

Here are photos of the café relocated so that its rear fronted on the shoreline of Portage Bay. In the second photo, a four is about to launch from a dock in front of the Varsity Boat Club.

In October 1912, the faculty approved this new facility for the women and officially sanctioned the sport again, provided that the women adhere to rigid conditions, presumably intended to keep Conibear on a short leash.

"The women shall dress at the gymnasium and report there before and after rowing. There shall be no racing at any time. This does not exclude form contests. The women shall not use the shells. The barges will be used, as is the custom in women’s rowing, to avoid danger."

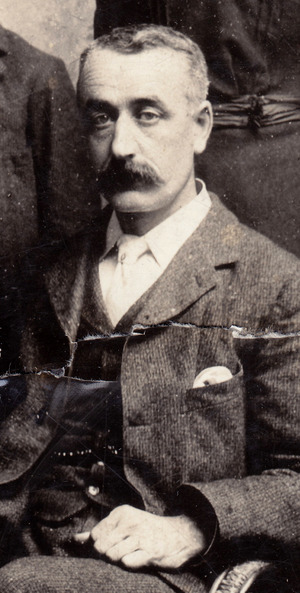

That fall of 1912, English master boatbuilder Aaron Pocock

joined his sons, Dick and George, on the upper floor of the Tokio Café, and they began building boats for the university and other customers. In December, the Pococks renovated the two women’s eight-oared barges so that they could resume rowing in the spring.

(This boathouse geography lesson will become more relevant in the second half of this presentation.)

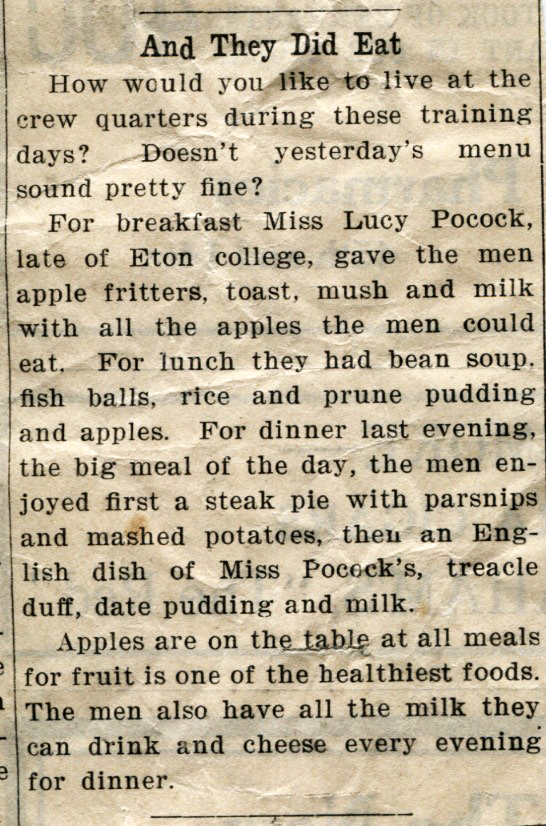

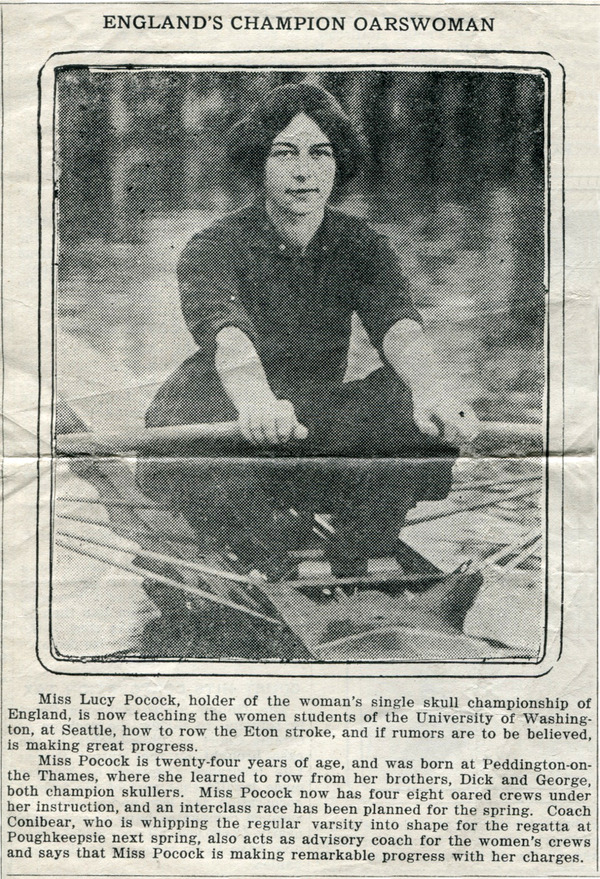

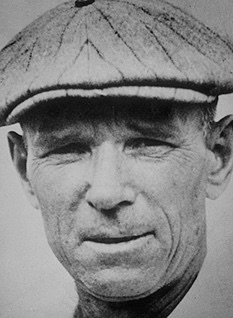

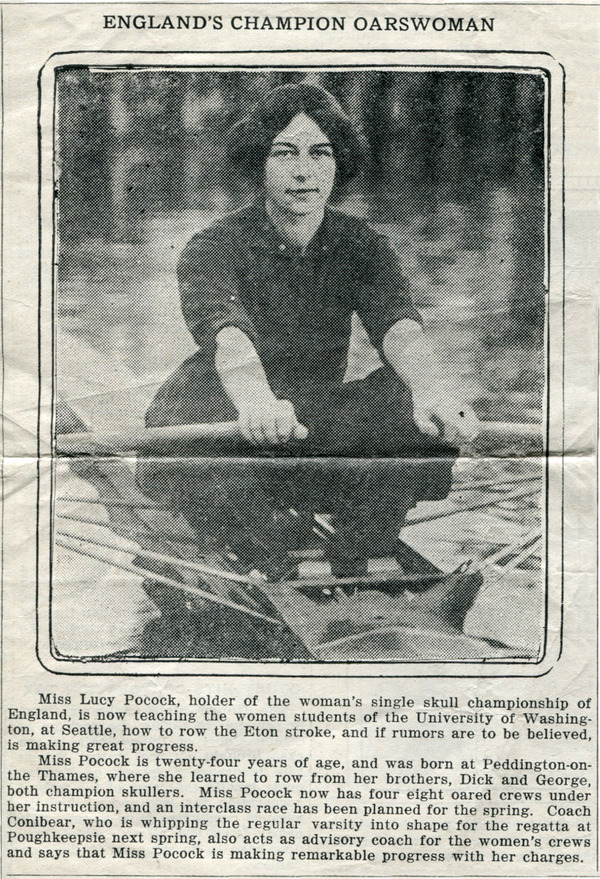

In the autumn of 1913, Lucy Pocock,

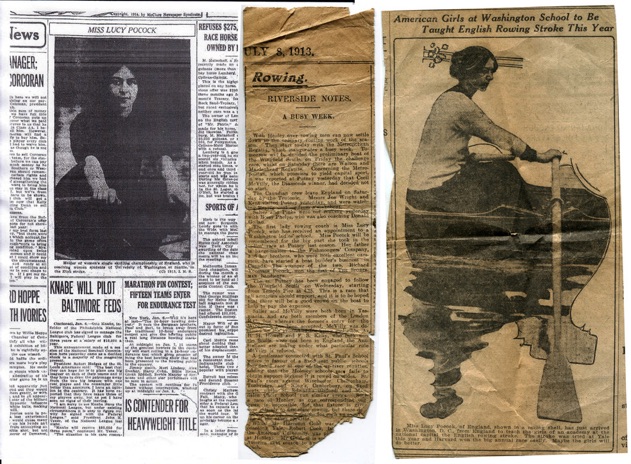

Dick and George’s older sister, who had been serving as cook for the men’s crew during the year since her arrival in Seattle with her father and sister,

Lucy was hired to coach the UW women’s crew. She was a famous oarswoman in her own right, 1912 Women’s Champion of the Thames, and thanks to the relentless promotion machine which was Hiram Conibear, much was made of Lucy’s appointment, with photos and newspaper articles across the United States and even in England.

A December campus newspaper article stated: "In the olden days, the water sport was a very popular one with the women, but was abandoned by the physical department, as the training was thought to be too heavy for the frail athletes. By much hard work on the part of those interested . . . and with proof the training was beneficial rather than harmful . . . the authorities have consented to the revival. The appreciation on the part of the girls was shown in the turnout which responded to Miss Pocock’s call."

Although Lucy Pocock only coached the women for a short time in the autumn of 1913, she was a wonderful role model and advocate and helped to reestablish the program at the UW at a very critical time. As I have mentioned, the second half of this presentation will deal with the Pocock family at much greater length.

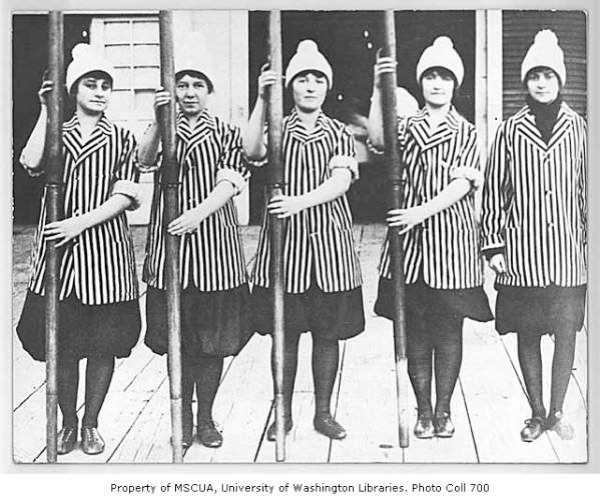

In September of the following year, 1914, there were 75 UW women signed up to row. They held a fall co-ed form-only regatta over three days in December, and more than 200 spectators cheered for their favorite crews.

The Juniors won the event. The Senior women, who had the best costumes –

"brightly striped blazers and white stocking caps" – won the fours contest, and at the end of the regatta, an all-star crew made up of women from each of the classes took a spin in one of the men’s eight-oared racing shells.

By the fall of 1915, crew was the most popular women’s sport on campus with 160 signed up. With much excitement they christened a new Pocock eight-oared racing shell of their own, aptly named the 1915 Co-ed, which they had purchased for $250.

One hundred women were rowing in the spring of 1916.

In June of 1916, Coach Conibear began a six-month suspension after a serious clash of wills with the new university president, Henry Suzzallo.

In later years, George Pocock remembered Conibear as "a bit of a meddler up on the campus." He would assiduously avoid or evade campus supervision . . . court the Seattle and the national press . . . and was directly cultivating local businessmen to fund his plans for the men to regularly compete in the national championship regatta back on the American East Coast in Poughkeepsie, New York. President Suzzallo would not tolerate such independence from any of his coaches. Only the intervention of Rusty Callow, the president of the student body and captain of the crew, persuaded Suzzallo to merely suspend and not fire Conibear outright.

Later that fall the president actually did fire legendary football coach Gilmore Dobie

who had not lost a game in 9 years and was a deity on campus.

Conibear spent the summer of his suspension attending the Poughkeepsie Regatta as an observer, speaking to coaches and studying the newest coaching techniques.

During 1917 in Conibear's absense, rowing was still the most popular women’s sport on campus as the United States entered the Great War that spring. The interclass form competition of May 1917 would be the very last regatta that the UW women rowers would participate in for over half a century. Over that summer, the United States Navy took control of the Tokio Café building for their use in training young men entering the service as the campus and the country shifted to a war footing.

On the morning of September 10, 1917, the day after he returned from his suspension, while picking fruit from a plum tree in his backyard, Hiram Boardman Conibear, fell, suffered a fatal head injury, and passed into legend.

After the war, with Conibear, their most constant and enthusiastic advocate, gone, there was no one left to fight for the women. And so after several near-death experiences, the first glorious flame of women’s rowing at the University of Washington was finally extinguished.

The City of Seattle and the University were growing up. The frontier spirit which had supported strong women and encouraged women’s collegiate rowing to take hold here was dissipating. The Great Depression and both world wars would further define and redefine women’s roles in society. It would not be until the 1960s and ‘70s that University of Washington women would again fight in earnest to regain the sports status that they had enjoyed during the early part of the 20th Century.

An historian is only as good as his sources. Many thanks to my good friend Bob Ernst, until recently the University of Washington’s Director of Rowing. Those who wish to delve further into UW Rowing History must visit Eric Cohen’s website, www.huskycrew.com, without question the best rowing history website on Earth and a shining example of what true passion can achieve. And special thanks to Ellen Ernst, who authored the sections on the women’s program. Consider my humble presentation just a taste, a small slice of what she has accomplished.

Part 2:

After our survey of women’s rowing at the University of Washington early in the 20th Century, let’s backtrack and examine a bit more closely the remarkable boatbuilding Pocock family, with special attention to Lucy Grace Pocock,

the UW women’s rowing coach during the fall of 1913, whose scrapbooks are now part of the collection of the River & Rowing Museum, thanks to the generosity of her granddaughter, Heidi Danilchik. Those scrapbooks, supplemented by Heidi's family recollections, form the foundation of this portion of my presentation.

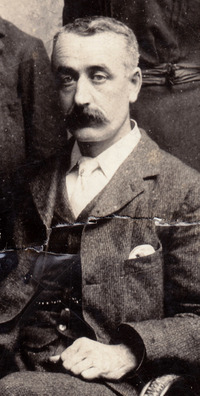

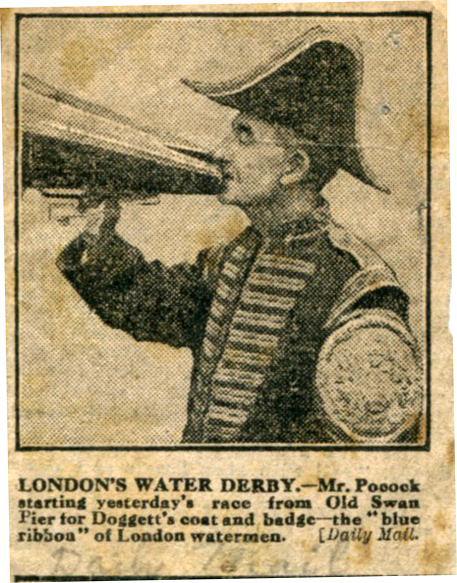

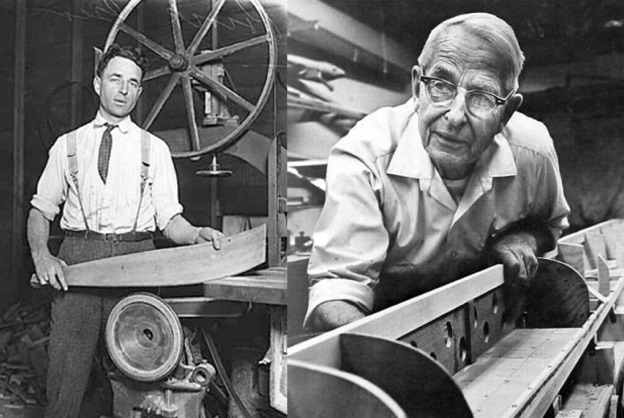

Lucy’s father, Aaron Frederick Pocock,

known as "Fred" to his friends, came from a famous family of Thames professional watermen.

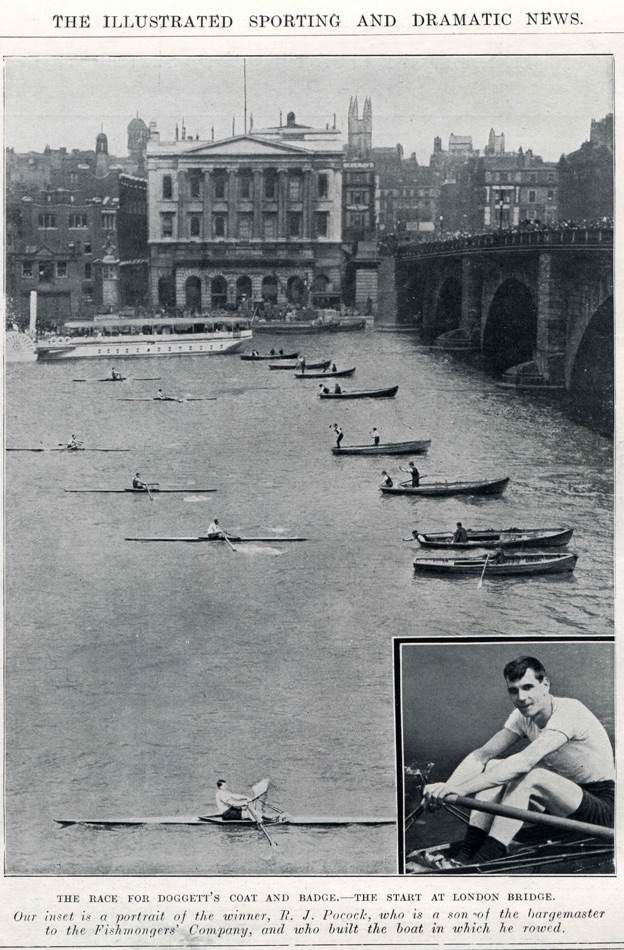

While his children were growing up, he was the boatman of Eton College. He was also Bargemaster to the Fishmongers’ Company, and as such, officiated the Doggett’s Coat and Badge Race, the world's oldest annual athletic competition.

He and his wife, Lucy Vickers Pocock, from another famous waterman’s family, had four children.

Heidi recalls: "Julia she was the eldest, born in 1885, and then Lucy in 1887, Uncle Dick in 1889 and Uncle George in 1891, but then their mother died. Fred eventually remarried, and then tragically Fred’s wife second wife also died giving birth to Kathleen, Aunt Kath, in 1895. Auntie Ju was sent out to be a companion, so that she wasn’t another mouth to feed, helping out her grandmother, Grandma Pocock. The family hired a series of god-awful housekeepers until Lucy was old enough to take over the child-rearing."

From the left in the picture above: Julia, Dick, Kath, George, Fred and Lucy.

From waterman stock on both sides, the Pocock children were handsome, strong, talented and tall, George eventually over 6’1”, Lucy 6’0” and Dick 6’5”. On Sunday afternoons in Eton, their dad used to love taking out a barge four with Julia in stroke, Lucy in 3, Dick in 2, George in bow, Kathleen coxing and Dad in the extreme stern. They used to race the river steamers traveling to and from Windsor Castle, across the Thames from Eton.

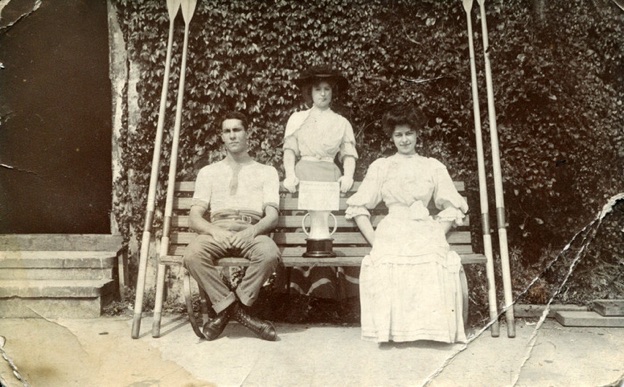

The first to excel in rowing competition was Lucy. In 1906 and 1907 when she was 19 and 20 years old, she won a number of Mixed Double Sculls events with H.N. “Blackie” Wakefield, and coxswain Miss S. Goertz, at National Amateur Rowing Association (NARA) regattas open to tradesman and artisans, including the Henley Town and Visitors’ Regatta both years and the Newman Challenge Cup for the Championship of the Thames at the Teddington Reach Regatta in 1906.

Here they are in September, 1906, posing in front of Rafts on the Eton riverfront.

Check out the same bench.

They are all dressed up with a copy of The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News describing their victory and the Newman Challenge Cup that they had just won.

And here they are posing on the same afternoon just off of Rafts with Windsor Bridge and the castle in the background. Incidentally, to this day the Skiff Racing Association still awards the same Newman Challenge Cup

to the annual winner of its Mixed Doubles Championship on the Teddington Reach.

Here is a photo of the 2008 race,and here are 2015 winners R. Hurley, R. Groom and Cox P. Cammack with the very same silver cup, 109 years after Lucy, Blackie and Ms. Goertz won it. Isn't that marvelous?

In 1907, Fred Pocock entered 16-year-old George in his first singles race, the Junior Singles event at a regatta at Henley United Rowing Club, an NARA club which no longer exists. He won first prize.

At that time, George and Dick were apprenticed in the boatbuilding trade to their father at Rafts on the Eton waterfront. They also often worked with Eton boys, including the future King of Siam, William Grosvenor, future Duke of Westminster, Tom Sopwith of aeroplane fame and Anthony Eden, future Prime Minister.

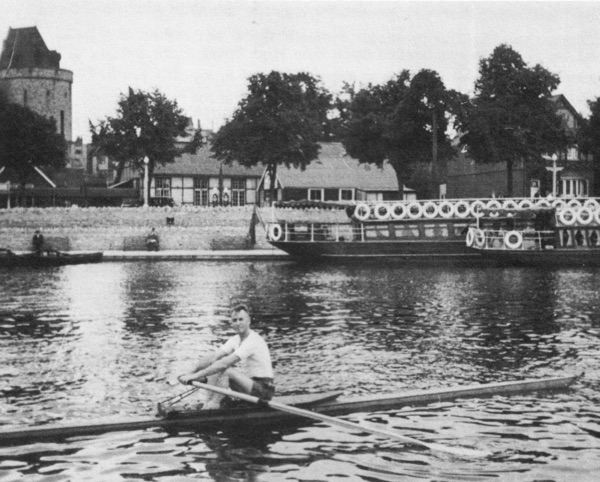

The following year in 1908, Fred entered 17-year-old George in his first professional singles race, the Championship of London, a handicap race, 2 miles from Hammersmith to Putney. There were 58 entries. For the occasion, George built his own shell with skin of blond Norway pine below dark mahogany washboards, the reverse color scheme of most wooden shells. After the 1936 Berlin Olympics, George returned to Rafts and rowed the boat again,

one of his favorite memories. The 28-year-old shell was still extremely popular with the Eton students. This 1936 photo was taken from Rafts with the Windsor waterfront and a bit of the castle in the background.

Back to 1908. George won his two rounds of elimination heats to qualify for the four-boat final, which included Charles Harding, a former champion of England. George was started 3rd, 2 seconds behind John Bowton, a policeman from Hackney, and Billy Coles from Erith, and 2 seconds ahead of Harding. The other three being from London, they knew well the infamous tricky turns and treacherous currents of the Tideway. Fred gave his son the following advice, "Now, Wag Harding knows this course blindfolded. He has lived on it. Be sure and keep him directly astern, and you will not have to look around."

George won by less than half a length over Bowton and received the very handsome sum of £50. His father had bet £5 at 20-to-1 odds and won £100 more.

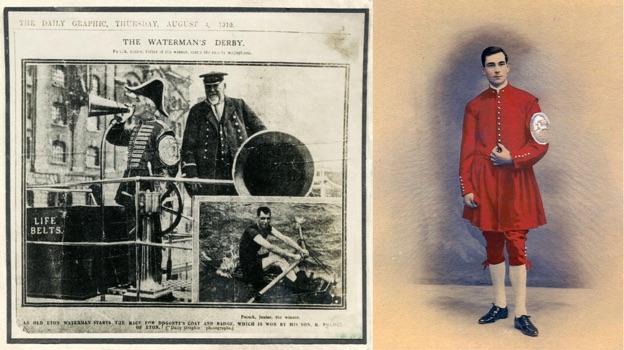

In 1910 in a boat of his own construction, Dick Pocock won Doggett’s Coat and Badge at the age of 21.

With his proud father officiating, he led from the start and was never headed. He and George had trained together all summer and sculled down through the locks to London from Eton the day before.

In 1911, with Dick having finished his apprenticeship, the two brothers decided to seek their fortunes in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, a place of booming opportunity for skilled craftsmen 150 miles north of Seattle. The trip was financed by the remains of the £50 purse that George had won three years earlier as winner of the Championship of London, for the rest of his life prompting him to say when asked, "I rowed my way from England to Canada."

They arrived on George’s 20th birthday with $20 in their pockets. It was in Vancouver where Hiram Conibear tracked them down a year later in 1912 and talked them into relocating to the Tokio Café in Seattle

in order to build shells for the University of Washington. Dick was 23 years old, and George was 21.

George had always intended to return to Britain briefly in 1912, the year he was eligible to row in Doggett’s Coat and Badge, but he had cut a finger off in a logging camp outside of Vancouver the previous year, so he abandoned his plan. He later confided to his son that he thought his world had come to an end. Several times George had beaten the man who eventually won.

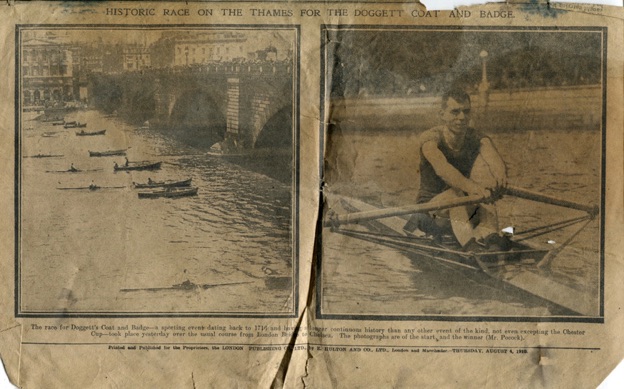

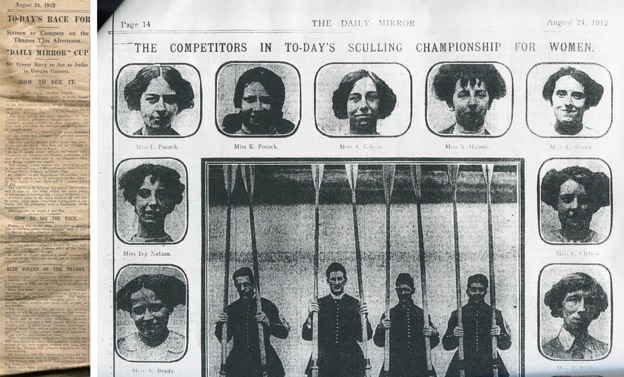

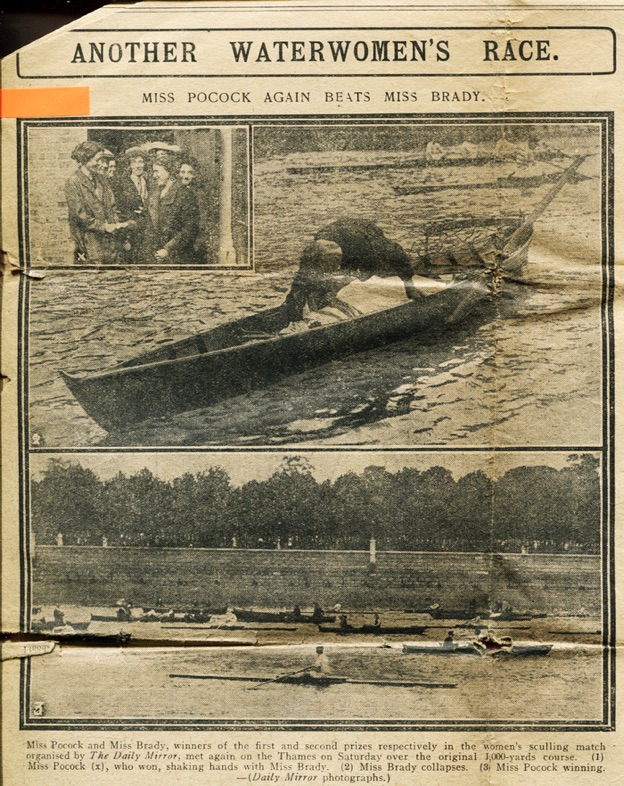

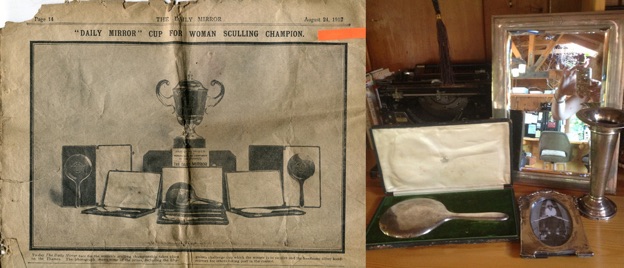

Instead, 1912 turned out to be Lucy Pocock’s year. On August 24th 1912, the graphic newspaper The Daily Mirror of London held "a Women’s Championship of the Thames . . . a unique opportunity for London’s women scullers to show that they can hold their own with the stronger sex in this finest of aquatic sports. Today’s great sculling match for women-only is a romantic revival of an old-time boat race, held on the Thames in 1833, for the wives and daughters of fishermen."

The boats were half-outrigger skiffs with none other than Doggett’s Coat and Badge winners acting as coxswains, and the distance was 1,000 yards from Craven Cottage Point, Fulham, to Putney pier. Five heats were held on Thursday, August 22nd, amongst 33 daughters or relatives of Thames watermen. Twelve, including both 25-year-old Lucy and her 17-year-old sister Kath,

qualified for the four Saturday afternoon semi-finals. Lucy won her semi and advanced to the final to be rowed 3 hours later, where her strongest competition would turn out to be

a Miss A. Brady from the Bermondsey neighborhood in the London Borough of Southwark.

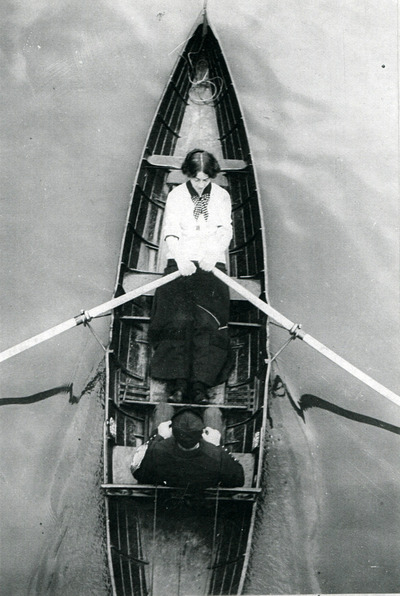

Here is Lucy before the start.

A crowd in excess of 25,000 assembled near the finish line and braved light rain to watch this unique race.

Brady in the lane nearest the camera got the best start, led by half a length immediately and maintained that lead after 200 yards. The photos reveal Brady to have been an aggressive but inelegant sculler.

Lucy in the next lane over left the stakeboats in last place. However, "sculling with fine judgment and style,"

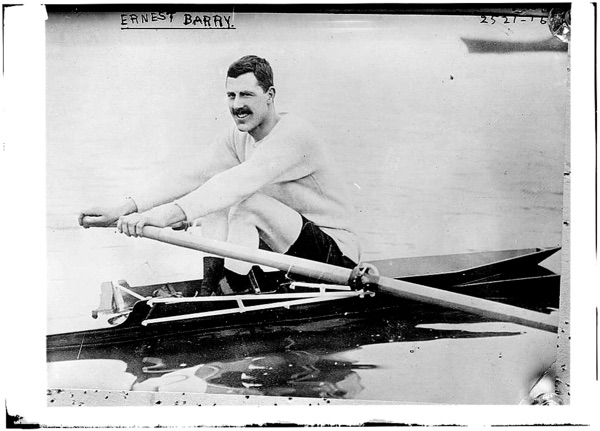

according to World Professional Singles Champion Ernie Barry, official judge of the match,

Lucy took the lead at the half-way point. With 300 yards to go, Brady caught a slight crab, and Lucy expanded her lead to a length. As they approached the finish line, "although very exhausted, Miss Pocock managed to keep the lead and won the race by less than half a length,

the finish being brought to a dramatic close by Miss Pocock collapsing in her boat and Miss Brady going immediately to her assistance to bring her round."

Here is Lucy, now recovered, rowing over to the huge crowd in front of oarmakers Ayling and Sons,

a building which still exists on the Putney waterfront today.

And here she is receiving The Daily Mirror Cup from Ernie Barry, described as "rather over 6ft tall." Lucy could look him straight in the eye, and both towered over her coxswain, a former Dogget's winner.

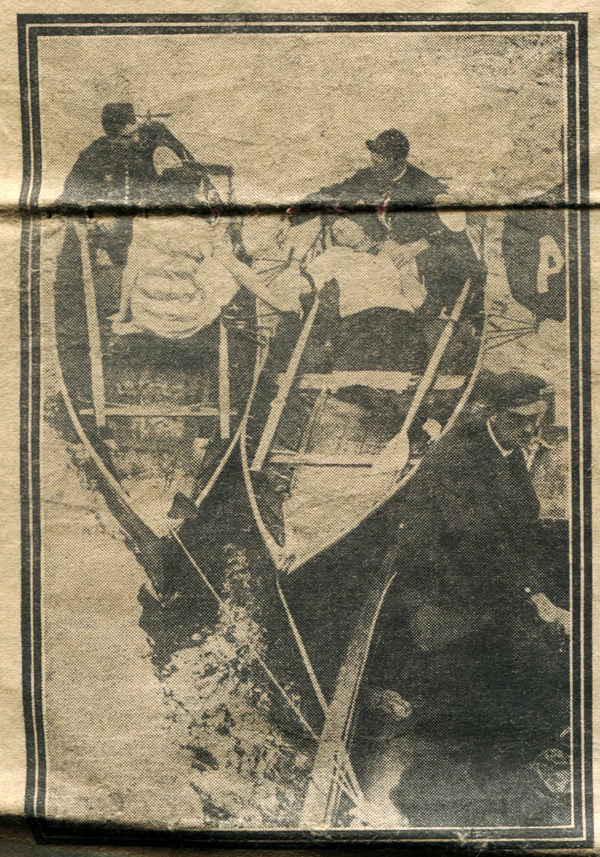

The race had been so popular that The Daily Mirror arranged a rematch between Lucy and Miss Brady.

Lucy won again, and this time it was Brady who fainted.

Besides the prize money, Lucy won a silver hand mirror for the first win and a silver wall mirror for the second.

And now the two halves of my presentation today truly join . . .

The prize money from the race and the rematch helped Lucy, Kath and their father join Dick and George in Seattle that October 1912. Fred went straight to work helping Dick and George build shells on the upper floor of the Tokio Café, and Lucy began cooking for the UW men’s rowing team with Kath as her helper.

Let’s return to our geography lesson. Looking south across campus, the Varsity Boat Club is circled. Note there is an isthmus beyond the old exposition grounds with Lake Washington to the East and Portage Bay, Lake Union and the open water of Puget Sound to the West. Back then, the level of Lake Washington was some nine feet higher than the level of Portage Bay. In the first decade of the 20th Century, all that connected the two bodies of water was a flume wide enough to funnel down newly-harvested logs on their way to sawmills in Seattle.

However in 1912, the land bridge southward was completely blocked by one of the largest construction projects in Seattle history, the digging of the half-mile-long Montlake Cut.

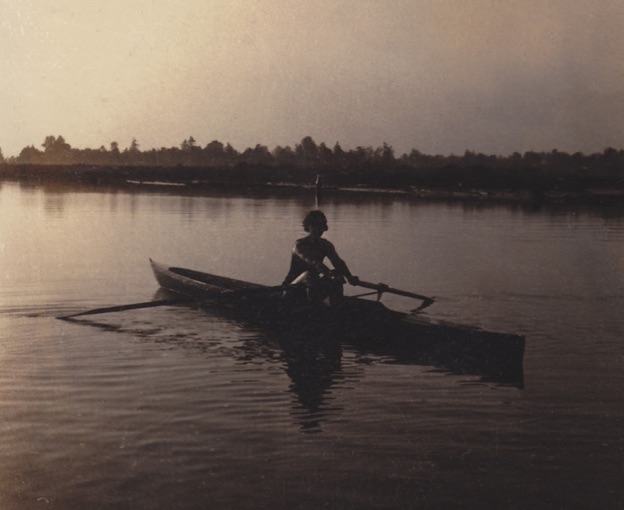

Every morning, Lucy would get into the single wherry that George had built for her and row across Portage Bay to shop for food for the men's rowing team at a farmers’ market on the other side.

Here is another map of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition site in 1909 looking northeast. Let’s focus on the lower right.

The blue star is the site of the old Coast Guard Lighthouse, now the Varsity Boat Club. The Tokio Café had originally been built at the first red star, at the foot of the Pay Streak. The second red star is where Conibear had it relocated. Right next door to these rowing facilities, the green star is the construction site for the Montlake Cut, known then as the Lake Washington Canal.

The construction company digging the Cut was Stillwell Brothers, one of Seattle’s largest and most experienced. The younger brother, James B. Stillwell was at the job site early each morning . . . and he became utterly intrigued by the sight of this lithe 6ft woman gliding effortlessly over the water right past him.

Heidi, Lucy’s granddaughter, loves this picture. This is what Jim Stillwell would have seen every day in the early morning sunlight.

According to Heidi, "Stillwell was a widower with three children at the time. It took him a while, but when he got to know her and found that she was cooking for the crew table, he said, ‘Aha! This woman can take care of my kids at home, too!’ They ended up getting married in 1917."

By the way, here is a photo of the Montlake Cut today, now the race course for Washington Husky crews and the venue for Opening Day.

In time, Lucy and Jim Stillwell had two children of their own.

Here is Lucy introducing Betty and Grace to her father in England in 1929.

Lucy lived until 1958, Jim until 1966. Grace’s daughter Heidi still lives in the Seattle area.

Kath

had a career working as a secretary for the State of California. She and her husband raised two children, and she never rowed again. She lived until the day before her 94th birthday in 1989.

Dick

moved to New Haven, Connecticut, in 1922. He and his wife Jesse had three children, and until he retired, he made about one eight-oared shell per year for Yale University, 42 in all, each one consecutively numbered at the coxswain’s seat.

The shell that won the 1924 Olympic Eights title for Yale was number 4.

Dick Pocock passed away in 1967.

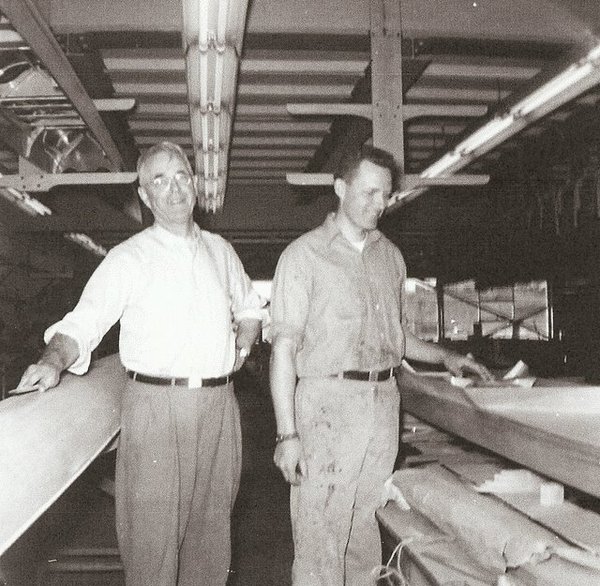

George

had a 54-year fairy tale marriage to his wife, Frances. They had a son, Stan, who eventually joined his father in the boatbuilding business.

George kept making wooden boats on or near the University of Washington campus until his death in 1976. When I began rowing in 1959, and this is no exaggeration, virtually every shell in every schoolboy and college boathouse in America . . . except Yale’s . . . had been made by George Pocock Racing Shells

. . . but that’s a story for another day.

Today the company George founded continues the family legacy.

Many thanks to Stan Pocock, who spent uncounted hours with me reminiscing about his family before his passing in 2014 . . . and extra special thanks to Lucy Grace Pocock Stillwell’s granddaughter, Heidi Danilchik, for keeping the memory of her remarkable family alive and fresh and for donating her grandmother’s scrapbooks and oars to the River & Rowing Museum in Henley-on-Thames in England, the hosts for this Rowing History Forum.